By Abdullah Samateh

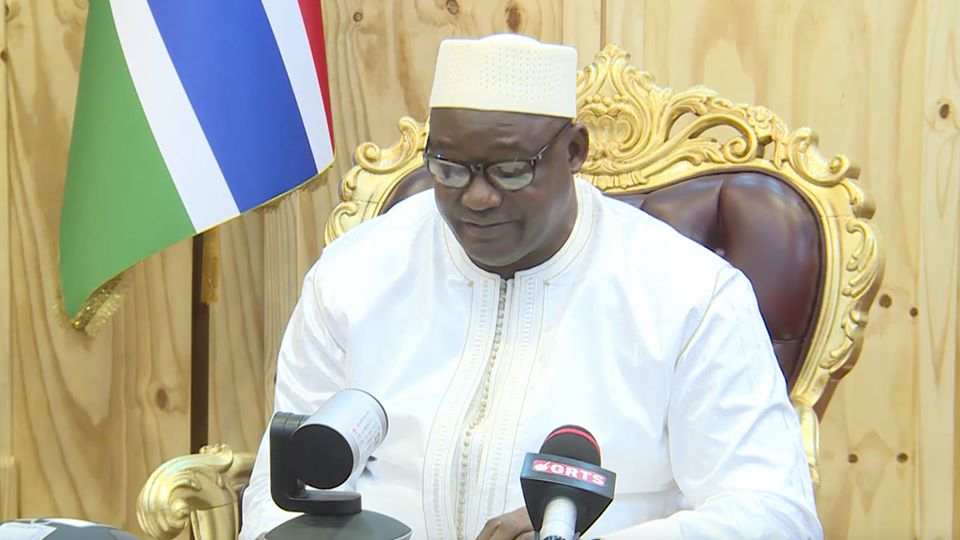

The coming to power of Mr. Adama Barrow as president of The Gambia marked the end of the darkest chapter in our history and revived hopes that a bright future was in sight. It meant a return to the ideals and values we hold as a people, but which remained elusive during the twenty-two year reign of Yahya Jammeh. While on the campaign trail, the then coalition candidate promised commitment to the restoration of those ideals and attainment of the nation’s long-pursued aspirations. No one at the time cast the slightest doubt on his determination to deliver on his promises. After all, Mr. Barrow was widely perceived as a comrade in the fight against oppression who experienced firsthand our tragic plight under the dictatorship. In short, Barrow was the living embodiment of the future the people envisioned post-dictatorship.

However, the dramatic events that followed his rise to power, culminating in the growing discontent the country is witnessing today, is a testament that this was a misplaced trust and a serious misjudgment of the man the people entrusted with their future. Today, the president that was once hailed as the people’s hero during the heydays of the coalition government is now widely viewed as the villain-in-chief. He stands accused of plunging the country into a quagmire of chaos and uncertainty, as a result of his incompetence and lack of political sagacity.

Indeed, Barrow is central to any gains made or loses incurred under his watch. Yet neither the gains nor the losses wouldn’t come to pass without the actions or inactions of other stakeholders. Logically, accusing fingers will be pointed at him as the Commander-in-Chief while political turmoil sweeps the country. However, other stakeholders should not be left off scot-free without being held accountable. In fact, one could argue that the missteps made by the coalition members and other influential players in Gambia’s political landscape have inadvertently invited the current predicaments. Their actions allowed Barrow a convenient space to work quietly towards the realization of his hidden agenda. These include the coalition’s failure to abrogate the Jammeh-era constitution sooner by expediting the drafting of a new one, the coalition’s disunity and subsequent disintegration, and the rise of partisan journalism in the new dispensation.

It’s indisputable that the coalition succeeded a regime that had left behind a legacy of bad governance, dysfunctional institutions, and a staggering economy. Thus, it came in with onerous burdens on its shoulder. In well-functioning democracies, the succeeding administration assumes office to build on the successes of its predecessor and move the country forward. In the case of The Gambia, the coalition had to clean up the mess it inherited and begin de novo. Under such undesirable circumstances, priorities should be determined by the urgency of the moment. Given that the Jammeh era constitution — the document that decides our fates — is fraught with loopholes, draconian and self-serving clauses, the coalition should have prioritized the drafting of a new constitution that reflects the true aspirations of the people and ensures swift justice for the victims of the previous government.

Whether the failure to do so was a deliberate move on the part of the coalition is debatable, but what is crystal clear is that President Barrow had a vested interest in delaying a new constitution.

During his 2017 meet-the-peoples tour, Barrow sent a veiled warning that the laws of Jammeh dictatorship, including the Executive Orders, were still in effect and he had them at his disposal. To show skeptics he meant business, he embarked on a firing spree of cabinet members — mainly his coalition partners — senior civil servants, and a sitting member of parliament whose loyalties, he believed, lied elsewhere.

He must have acted out of firm belief that the dictator’s constitution empowered him to rule as he wished. Since then, he has committed numerous, glaring legal blunders in his quest to assert his authority and cling on to power. His actions have often sparked firestorms of outrage and created deep divisions within the country. Regrettably, Mr. President cannot be denied taking ‘controversial measures’ that are in line with the provisions of that constitution, even whereas they provoke public indignation.

Thus, a new constitution would have curtailed Barrow’s controversial powers, delivered justice to the victims and deterred corrupt practices. It might have even stipulated the transitional term to be served by him. In other words, a new constitution would have spared the nation much of the noise triggered by the president’s actions. Interestingly, that unique moment to draft our dream constitution presented itself while the coalition was still a united front. In fact, it’s public knowledge that the coalition had among its ranks the finest legal minds and renowned human rights advocates, who could have produced the people’s constitution within a short span of time. Its failure to identify this as an urgent priority and our collective silence have contributed to the emergence of the status quo.

Equally, the rise of partisan journalism in the new dispensation — precisely in the build-up to the legislative and municipal elections — is in my view one of the underlying causes of the existing situation. This was the period when the political climate became sharply polarized over the best winning formula the coalition needed to adopt. It was apparent that the coalition members were on a collision course. The traditional role of the Fourth Estate is to represent the diverse voices of the people and hold the leadership to account. Strangely, this core value of media profession came into the peripheral vision of ‘some’ media practitioners during that critical period of our history. They chose to act as the mouthpiece and frontline fighters of their party leaderships or those they sympathize with amid the political tensions. So, the tensions heightened and division took root since then.

Similarly, ‘some’ civil society members, who are prominent members or sympathizers of certain political parties, were seen to be representing the interest of their parties and, as a result, lost listening ears among their opponents. Their fiery rhetoric and constant criticisms of other political leaders, while sparing their own arouse suspicions that these organizations were being used by ‘some’ to attain political ends.

Consequently, instead of promoting convergence of views and preventing the coalition from disintegrating at that critical moment, they partook in exacerbating political animosity amongst the rivals. In fact, the level of mistrust reached a point that propositions put forward by one political party, however genuine and practical, were perceived by others as a premeditated move to score some political points. The principle that ideas should be gauged on the basis of their merits and not who advanced them was flouted time and again. This is how partisan politics poked its ugly nose into the politics of our transition period at a surprisingly early stage. One would have expected that the unity of purpose and pursuit of the greater good that brought the coalition to power would reign supreme throughout the transition, not partisan politics that took over almost from the start. Worse still, the same pattern of politicking continues unabated.

Finally, President Barrow was, at his election, a novice leader, who was devoid of political knowledge. But to give credit where credit is due, he never tickled our ears, if anything he was very forthcoming about his slender governing background. He allayed our fears, however, by assuring us that the country was in safe hands thanks to his coalition partners, including erudite scholars and seasoned politicians who would help guide us to the Promised Land. In essence, President Barrow unequivocally informed The Gambians that the country would be collectively run by the coalition members despite him being the president. His utterances were received by his colleagues with a silence of consent, without expressing reservations or objections. Thus, it would only be fair for the successes and failures of the coalition to be attributed to all the constituting members. Now that things have started to fall apart, if Barrow is blamed for plunging the country into chaos, his estranged colleagues should equally be blamed for dereliction of duty. We must not be oblivious of their role in the difficulties we are experiencing today. Remember, after the rift had widened among the members in the wake of local elections, some of his partners distanced themselves from the coalition. They then shifted their energy toward fishing for and exposing every misstep made by him without offering alternatives. Others continued to defend his actions; achievements and blunders alike, saying they wouldn’t abandon one of their own at any cost.

As we can see, the coalition’s failure to mend fences and rise above their differences created a virtual power vacuum that allowed Barrow and his loyal underlings to work towards the realization of his hidden agenda. As political rivalry gained momentum, Barrow reached out to enablers of the former regime and a coterie of other opportunists that were ever willing to do what they do best: grooming a dictator and plundering our meager resources. Barrow could have been denied the time and space to do the damage he has already done if the coalition members remained united.

Yes, hold him accountable for the terrible situation we have found ourselves in, if you must. But do not spare his coalition partners and other key players. They are equally guilty.

In short, our current predicaments are the result of a collective failure. And the situation calls for a thoughtful reflection on our own attitudes and approaches, putting aside our emotions and biases to see where we went wrong as a nation. If we do, we can avoid the recurrence of such mistakes including future Jammehs and Barrows.